(above: “Immigrant Mother Raises Her Sons for Industry,” photo by Cynthia Teramae)

The Maxo Vanka Murals at St. Nicholas Catholic Church

24 Maryland Ave.

Millvale, Pa. 15209

http://www.vankamurals.org

Open: Saturday tours at 10:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m.

Admission: free, donations accepted

St. Nicholas Croatian Catholic Church, established in 1894, is the first Croatian church in America. The present structure was built in 1922 on Bennet Hill in Millvale, Pa., which was one of many mill towns along the Allegheny River where immigrants flocked from around the world to work in the steel mills and coal mines.

The church is unassuming until you enter and behold a historically significant story of the building of America and in particular, one of the build up of the city of Pittsburgh in its early industrial stage.

Beginning in 1937, pastor Father Albert Zagar commissioned Croatian artist Maxo Vanka to cover the interior walls of the church with murals. The works were done in two stages, the first resulting in eleven murals focusing on the main themes of the Croatian immigrant life in the old and new worlds, while the second set of fourteen murals, painted in 1941, focused more on social injustice and the inhumanity of war. Today the church and the murals are listed on the National Historic Register.

“I painted so that divinity in becoming human, would make humanity divine.”

Maxo Vanka

The Society to Preserve the Murals has in recent years raised enough money to begin restoration of the murals to almost their original brilliance. Currently they are continuing that work as well as installing state-of-the-art LED lighting to ensure visitors have a superbly lit experience.

Vanka called the murals his “Gift to America.” They tell the story of the Croatian immigrant experience where Pittsburgh was built on the backs of low-paid workers and where mothers lost their sons in industrial accidents.

One mural tells the story of an actual industrial accident of that time where four brothers were lost in a Johnston, Pa. mining accident. Another mural depicts holy women crying for those lost in war, while the mother sits at her dead son’s side. In the distance on a small hill, is St. Nicholas Croatian Catholic Church.

Other murals show an American capitalist being served a sumptuous dinner by a black servant, while on an adjacent wall, the scene shows a Croatian working family of that period in Pittsburgh sharing a simple meal of bread and soup while Christ stands in the background as protector.

In this, his most important work of art, Vanka merged traditional Croatian folk art with other artistic elements to including Mexican muralism, European symbolism and surrealism. This art is his legacy and a lasting tribute to those who gave their lives in the building of America and in the wars that would fracture his homeland forever.

Maxo Vanka’s Gift to America

an essay by Cynthia Teramae

The first Croatian parish was established in the city of Alleghany in 1894. The parishioners were made up of Croatians from the local communities of Etna, Lawrenceville, Millvale and Allegheny who were recruited from their homeland to work in the steel mills and coal mines of Pittsburgh. That original parish grew so large that it split into two sister churches under one parish. The original church moved to Millvale and still carries the name of St. Nicholas Croatian Catholic Church. It is located at 24 Maryland Ave., and is the home of the world famous Millvale Murals painted by Maxo Vanka.

The church now sits on Bennet Hill in Millvale and is the second church built at that site. The original built in 1900, burned to the ground and so the present church was completed in 1922 by architect Frederick C. Sauer.

To this day, people flock to the current St. Nicholas Croatian Catholic Church in Millvale to see these artworks first hand, but many may not know that this church had a sister church built by the same architect, Sauer. This church was also part of the original Croatian parish which began in 1894, but was built in 1904. Over the years, there has been much confusion of which church is indeed the first, but it was in fact the church located at 1326 East Ohio Street in the Troy Hill neighborhood of Pittsburgh that preceded the now famous Millvale church with its Vanka murals.

The Troy Hill church sat at the foot of the hill along the Allegheny River. The church had three prominent “onion domes” and beautiful stained glass windows made by Film Arts and Glass Company of Columbus, Ohio. The windows depicted the Croatian patron saints of Cyril and Methodius along with other saints. Croatian lodges from around the country sponsored the windows, and they were considered the focal point of the church.

This beautiful and historically significant church was added to the list of the City of Pittsburgh Historic Sites; however, in 2004 a broken boiler led to the closure of the church and the parishioners moved to other churches, including the present-day Millvale Croatian church.

This beautiful and historically significant church was added to the list of the City of Pittsburgh Historic Sites; however, in 2004 a broken boiler led to the closure of the church and the parishioners moved to other churches, including the present-day Millvale Croatian church.

View of Saint Nicholas Church in Troy Hill. It was declared a historic landmark by the city of Pittsburgh on July 13, 2001. (Luke Swank,; Circa 1920-1930, Carnegie Museum

of Art Collection of Photographs.)

After the Troy Hill closure, a 15-year battle between former parishioners who wanted to save the structure, the Catholic diocese, who owned the land, and the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, who had a plan to widen Route 28, ensued.

During this time plans were discussed to save the church. The Preserve Croatian Heritage Foundation was formed to save the church and they discussed turning it into a museum however that plan never came to fruition and the church was demolished in January 2013. It was noted as one of the ten historic sites lost in 2013 by the National Trust for the Historic Preservation.

However, the St. Nicholas Croatian Catholic church in Millvale still stands as a testament of the contribution of the Croatian immigrants to America and the murals, painted by Croatian artist Maxo Vanka, were to become his most significant life’s work.

Born in Zagreb, Croatia in 1889, Maximilian (Maxo) Vanka is thought to be of Austro-Hungarian nobility, but he never met his real parents. He was raised instead by a peasant woman, Dora Jugova, who taught him to be humble and have sympathy for the less fortunate.

Growing up in his homeland, he saw much upheaval and war, and it is that troubled history of his nation that influenced Vanka’s life and work.

He began his studies at the School of Arts and Crafts in Zagreb under the Croatian painter Bela Csikos-Sessia. Later he studied at the Royal Academy of Beaux Arts in Belgium. A lifetime pacifist, he joined the Belgium Red Cross in 1914 during World War I and saw first-hand the horrors of war. This experience had a deeply profound and spiritual effect on Vanka, and it influenced all his future art to include the murals in Millvale, Pa.

After the war, Vanka took a position teaching art at the Zagreb Academy of Fine Art. There he met his future wife, but also he immersed himself in the study of people. “He deeply understands village life and its soul,” Nikola Vizner wrote of Vanka. “The passive suffering and happiness which are intertwined in life. Vanka comprehends the deep, natural mysticism and religiosity of peasants.”[i]

Seeking a safe harbor, and for professional reasons, he made the decision to immigrate to the U.S. in 1934 with his American-born Jewish wife Margret Stetten, and settled in New York City.

Vanka’s arrival in the U.S. coincided with the Depression and during a trip around the Northeast and Midwest, he studied and drew the people he saw on the streets. “He seemed to inevitably gravitate toward the lowly, dirty, degenerate and neglected,”[ii] his good friend and traveling companion Lewis Adamic wrote.

Vanka was a close observer of everyday life, and he put a face on the poor and impoverished and gave them a voice. He had the “gift of sympathy,” toward mankind, and this would eventually lead him to Pittsburgh, Pa., leaving his mark of sympathy on the walls of the St. Nicholas Croatian Catholic Church.

Father Albert Zagar wrote to Vanka after seeing his work in an exhibition in Pittsburgh and asked him to cover the interior walls of the humble Millvale church. He gave him full artistic freedom, but asked only that he depict religious characters with a connection to their native land Croatia.

Vanka accepted and set to work on the first of 12 murals in April 1937. He worked from 9 a.m. to 2 a.m. for eight weeks.

In May 1941, Vanka moved his family to a farm in Rushland, Bucks County, Pa., and soon after he received another letter from Father Zagar to complete his work. “My walls have claimed me,” said Vanka, “every inch of the church must be painted.”[iii]

He completed a total of 25 startling interpretations of art depicting faith with the main themes of the Croatian immigrant family life, social injustice and war. Today the church and murals are listed on the National Historic Register.

The Society for the Preservation of the Murals was formed in 1990, and has in recent years raised enough money to begin restoration of the murals to almost their original brilliance. Currently they are installing state-of-the-art lighting to ensure visitors have a superbly lit experience.

Vanka called the murals his “Gift to America.” The murals tell the story of the Croatian immigrant experience where Pittsburgh was built on the backs of low-paid workers and mothers lost their sons in industrial accidents.

In one mural entitled “Immigrant mother raises her sons for Industry,” a mother is shown bending over her dead son in a Pieta-like style. The mural depicts an actual industrial accident of that time where four sons were lost in a Johnston, Pa. mining accident. In these murals, Vanka shows his sympathy for those lost in war while depicting both the horrors of war and those who lost their loved ones.

“Croatian mother raises her son for War,” depicts holy women crying, while the mother sits at her son’s side. In the distance on a small hill is St. Nicholas Croatian Catholic Church.

(photo by Cynthia Teramae)

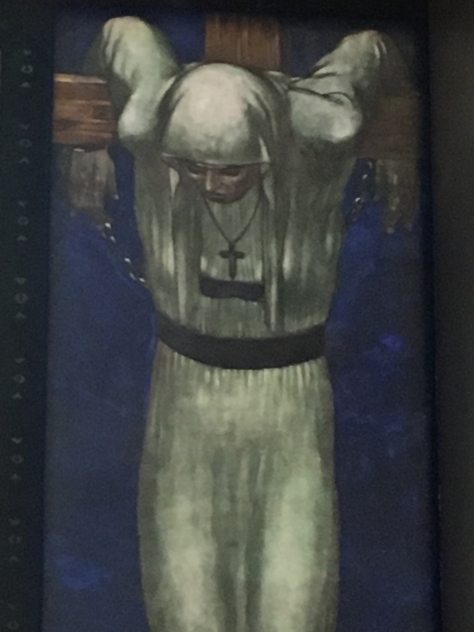

He painted Moses with his tablet clearly stating in the Croatian language, “Thou Shalt Not Kill.” In a mural entitled “Mati 1941,” he paints a 15-foot-high Croatian mother chained to the cross, while other murals show the horrors of war with Mother Mary on the battlefield breaking a soldier’s weapon, while still another depicts an astonished soldier who has mistakenly stabbed Jesus with his bayonet.

“The Capitalist,” depicts an American capitalist being served a sumptuous dinner by a black servant. On an adjacent wall, the scene entitled “The Simple Family Meal,” shows a Croatian working family of that period in Pittsburgh sharing a simple meal of bread and soup while Christ stands in the background as protector.

He was praised in the media for his work and shown much gratitude by the Croatian community throughout the U.S. Vanka noted, “These murals are my contribution to America – not only mine, but my immigrant people’s who also are grateful, like me, that they are not in the slaughter in Europe.”[iv]

(Mati 1941, photo by Cynthia Teramae)

Works Cited

“The Murals of Maxo Vanka.” The Society to Preserve the Millvale Murals of Maxo Vanka.

Web. [http://vankamurals.org]

“St. Nicholas Croatian Catholic Church.” Fr. Jim Mazurek. Web.

[http://www.stnicholascroation.org/our-history.html]

“Gaping hole signals former St. Nicholas Croatian Catholic Church’s demolition.” Mathew Santoni. Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. (January 13, 2013).

“Local Historic Designations”. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation. Retrieved 2016-10-24.

Leopold, David, ed. The Gift of Sympathy: The Art of Maxo Vanka. Doylestown, Pa.: Piccari Press, 2001. Print.

Notes

[i] Nikola Visner, Homeland, The Gift of Sympathy, The Art of Maxo Vanka, 14.

[ii] Louis Adamic, My America 1928-1938 (New York, Harper Brothers, 1938) 164.

[iii] David Leopold, Pictures of Modern Social Significance., The Gift of Sympathy, The Art of Maxo Vanka, 32.

[iv] Ibid, 34.